On International Law

Self-Defense vs. Horrific War Crime

Amid another round of Foreign Policy Enforcement targeting Iran, the moment seems appropriate to revisit a key point: “international law doesn’t work.” The issue is not that it fails to function — but that its purpose is consistently misunderstood. International law, as imagined by millennials, has never operated as they assume. Nor was it designed to.

Caustic references included.

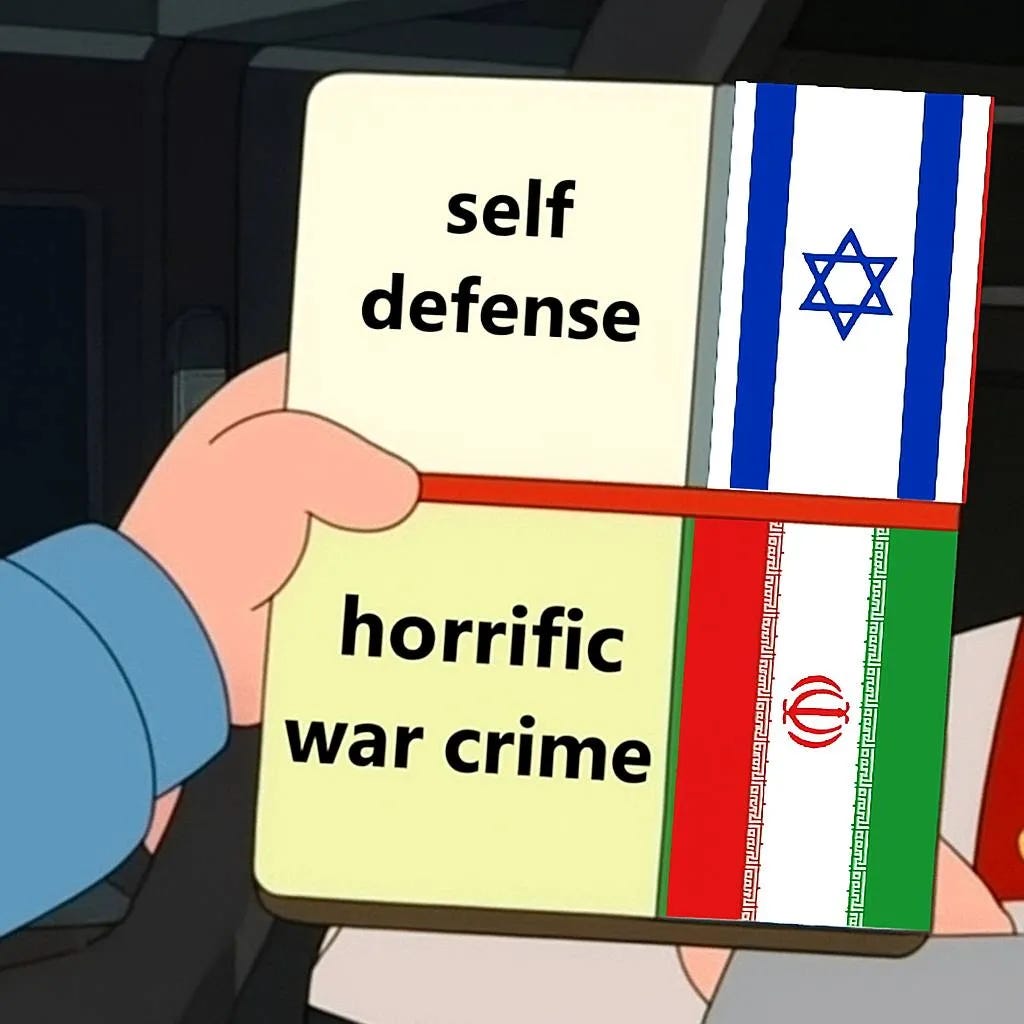

A meme explains how international law functions more clearly than most academic essays.

In its extended version, the meme reads:

self-defense: WEST

horrific war crime: REST OF THE WORLD

The formula “self-defense” for some and “war crime” for others is not a meme about hypocrisy. It is a compact diagnosis of how agency is distributed in the international system. Not a situational error — a structural feature.

The Source Is Not Double Standards — It’s the Architecture of Sovereignty

By the late 19th century, European powers had codified a standard: a full legal subject is a “civilized” state. All others are objects of administration. The Berlin Conference (1884–1885) institutionalized this via the right to violence under the guise of “civilizing missions.” Sovereignty was never granted as a universal condition — it was always a graded internal status. That logic didn’t vanish; it only changed its language.

The UN Charter and the Rome Statute Did Not Replace the System — They Supplemented It

The formal ban on force (Article 2(4), UN Charter) is neutralized by an exception: self-defense (Article 51). Who decides when that exception applies remains unspecified. The ICC — nominally a universal institution — excludes from its jurisdiction those who govern the system: the US, Israel, China, Russia. At the same time, the power to define threats and initiate interventions remains with the same set of actors.

Legal Enforcement Tracks Power

There’s a warrant for Putin. There’s one for Netanyahu too. Enforcement is selective. Mongolia (a member of the ICC) did not detain Putin; the Court recognized the non-cooperation but took no further steps. International law is not an autonomous machine — it is embedded in a network of political dependency.

Who Has the Right to Use Force

The legal subject authorized to use violence emerges from European philosophical categories: reason, autonomy, order. Those who do not match the template are rendered “non-subjects.” This is not a bug; it is the core access criterion. First comes the subject entitled to define order, then the norm declared as universal1.

Responsibility to Protect Does Not Eliminate Asymmetry — It Legalizes It Through a New Rhetoric

The 2005 World Summit introduced the “responsibility to protect” formula. In practice, it is applied by the same actors who operate outside constraints. Universality remains declarative. Enforcement still tracks status — what matters is not what was done, but who did it.

Conclusion

The structure of violence distribution remains colonial in form and institutional in function. The right to “self-defense” is not a precedent — it is an asset, held by a select few. This is why the meme works: it is not hyperbole, but a compressed ontology of a system where the label “war crime” follows not the act, but the passport.

This is the actual international law often invoked by liberals and leftists of various shades — typically without any grasp of how it operates.

Departing from the current framework is not an emotional question. It is a matter of institutional capacity. Preferred methods among this audience — foot-stomping, yelling “How dare you?!”, gluing oneself to asphalt, or staging tragedy on Instagram — do not shift structural arrangements. Neither does a full-scale war with hundreds of thousands dead in muddy trenches.

If anything shifts the frame, it is the accumulation of power, time, and subjecthood. Even the globalist project and its “end of history” did not shift the boundaries — the proclaimed universality came with exceptions carved out for legacy centers. The frame remained intact.

What we observe today is a contest over access to varying degrees of exclusivity at the table. Personal ambition, when substituted for statecraft, becomes a structural liability. ■

Heidegger showed that any engagement with being already presupposes a choice of ontology. Whether the sovereign act of the “other” is recognized or denied is not a moral decision but an ontological one, masked as ethics.

Schmitt argued that the sovereign is the one who decides on the state of exception. In the present configuration, this position is occupied by the United States and its allies — they define when violence is legitimate.

Gramsci explained how hegemony operates through culture and norms, constructing the appearance of “natural” order. As a result, Western violence becomes illegible as violence.

Anghie demonstrated that sovereignty did not emerge in parallel with colonialism, but through it — as the right to exclude.

Mbembe shows how the figure of the “rational human” functions as a filter: those who do not conform are excluded from the zone of protection.

Pahuja argues that universality is not neutral — it is structured around an exportable model of development in which norms serve the center, not the universal.